Wisconsin as a destination for Germans

The first German settlers in Wisconsin arrived in 1839 and were part of organized groups fleeing religious persecution in Germany. The original group numbered about 1,000 and left Germany in 5 American ships. About one half of this group settled in Buffalo, NY and the other half settled in Wisconsin. The Wisconsin settlers bought land along Lake Michigan on the northern side of Milwaukee. About three hundred of this group bought land west of Mequon and started a colony they called Freistadt (Free State), which still exists as a town between Mequon and Germantown.

In 1843, a second large immigration was organized, again due to religious persecution. This group settled partially in Milwaukee and in counties surrounding Milwaukee.

During the mid 1800s, many of these original immigrants sold their land and moved to Sheboygan and Manitowoc counties, where land was more plentiful and less expensive. Also, to spur more immigration, two of the initial group of immigrants, Captain von Rohr and Rev. Johannes Grabau toured Germany to ‘talk up’ the benefits of immigrating to Wisconsin. Immigrant letters home to relatives still in Germany highlighting the success of life in America encouraged more immigration among family and friends. While it is unknown exactly why the first Gottsacker immigrant, Charles/Carl Sebastian Gottsacker came to Wisconsin, letters from those who had previously immigrated, combined with crop failures in Mayschoss, religious persecution and general political problems in Germany certainly must have been influences.

Another big advantage of Wisconsin to German immigrants was an established common language–German–a common heritage, and common customs all of which made the transition from Germany to America easier. At one point, there was even an effort to make Wisconsin a German state where German customs and institutions would rule the land. That effort failed miserably. Plentiful work both on farms and in a thriving and growing industrial base meant consistent incomes. The climate was similar to that of Germany and the crops were the same as those grown in Germany. A growing immigrant population also meant increased demand for craftsmen to make, create, and build.

Why they left Mayschoss

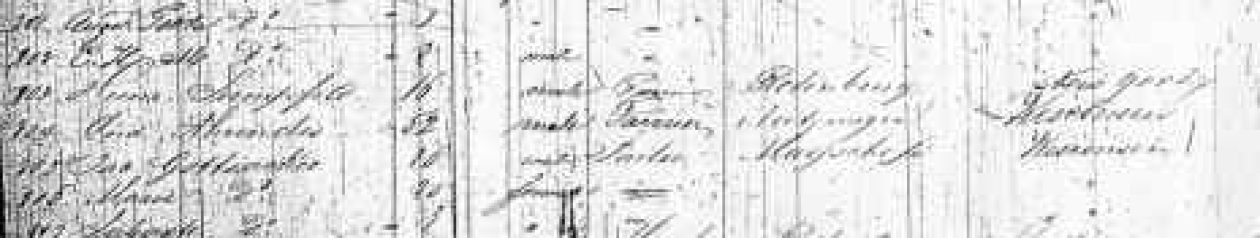

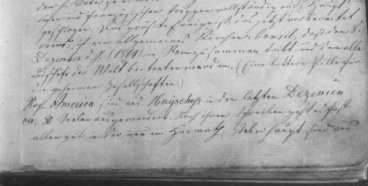

Most villages in Germany maintain a village book or chronicle of finances, events and the like. Mayschoss has such a book and during one visit I was fortunate to be able to look through the book. These village books are typically very, very old and fragile. A relative of the Mayschoss Gottsacker family , Hubertus Kunz, was mayor (burgermeister) at the time of our visit. Hubertus brought the village book in an aluminum case to Franz’s house so we could look for any evidence of Gottsacker emigration. Below, a notation in 1864 indicated that ‘many souls’ had left Mayschoss for America. The village book also notes that there were bad harvests from 1849 to 1854. In 1854 what looked to be a great harvest was destroyed by an early frost on May 4th. As mentioned above, there had also been political unrest in Germany aimed at liberalizing the constrained political and social life of Germans and this liberalization effort had largely failed. Gottsacker family stories indicate the family favored the liberalization effort.

Leaving Germany

It is not difficult to imagine the combination of heartbreak and excitement felt by German families who watched their kin depart for America. Carl Shurz, a German immigrant, and a leading Wisconsin politician in the 1850s, characterized this situation in a speech: “It is one of the earliest recollections of my boyhood that one summer night our whole village was stirred up by an uncommon occurrence…One of our neighboring families was moving far away across a great water, and it was said they would never return. And I saw silent tears trickling down weather-beaten cheeks, and the hands of tough peasants firmly pressing each other, and some of the men and women hardly able to speak when they nodded to one another a last farewell. At last the wagon train started into motion, they gave three cheers for America, and then in the first gray down of morning I saw them wending their way over the hill until they disappeared into the shadowy forest. And I heard many a man say how happy he would be if he could go with them to that great and free country where a man could be himself.“

Coming to America

The journey to America was long and difficult. In the 1850s, about the time most Gottsacker immigrants came to Wisconsin, the cost of passage between Bremen and New York was $16.00 and the journey typically took 96 days. Some ships arrived with little food or water remaining. On a visit to Milwaukee in 1843, Margaret Fuller noted “The torrent of emigration swells very strongly toward this place. During the fine weather, the poor refuges arrive daily in their national dresses all travel-soiled and worn. The night they pass in rude shanties, in a particular quarter of the town and then walk off into the country–the mothers carrying their infants, the fathers leading their children by the hand…Who knows how much of old legendary lore, of modern wonder, they have already planted amid the Wisconsin forests.” Starting a new life in a new country must have been an awfully difficult strain. It makes sense that in Gottsacker immigrant families, the men came to America first, settled, and then a year, two or three later, sent for the remainder of their family. This was also common in most German immigrant families.